Justin Price discusses the typical causes and contributors to rotator cuff injuries, and what you can do as a fitness professional to help clients to overcome this common problem.

One in five people will experience a rotator cuff strain, tear or injury at some point in their life1.

Staying within your scope of practice

It is not appropriate, or your job, as a fitness professional to diagnose a rotator cuff injury. That is the responsibility of licensed medical professionals who are trained in the assessment and diagnosis of such conditions. However, because many of your clients will come to you with this diagnosis, it is your responsibility (and well within your scope of practice) to understand the function of the rotator cuff, how this area of the body is typically injured, and what you can do to address your client’s underlying musculoskeletal issues to help alleviate such a condition3.

What is the rotator cuff?

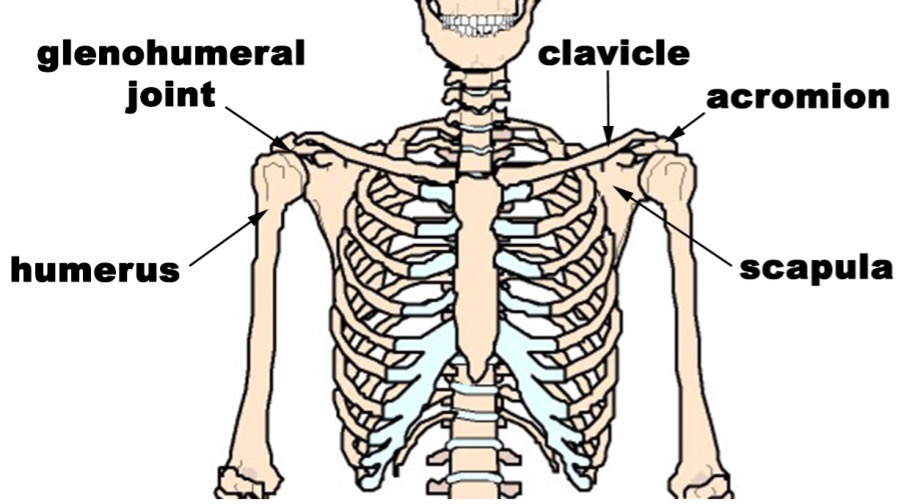

The glenohumeral joint of the shoulder is formed where the end of the upper arm (i.e., humerus) comes together with the outer edge of the shoulder blade (i.e., scapula) (see Figure 1)4.

Figure 1: Bones of the shoulder

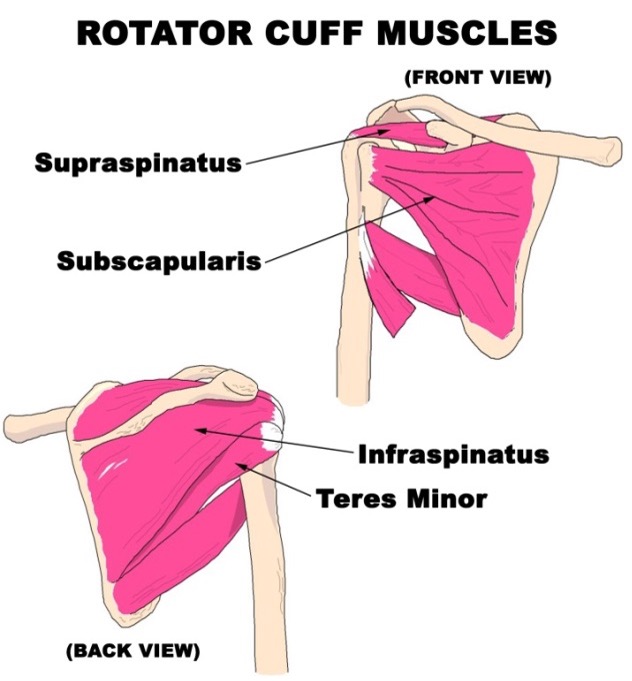

The glenohumeral joint is a ball and socket joint that allows for great range of motion, in part due to the smooth cartilage that lines it. While there are many muscles that attach to the arm (e.g., deltoids, pectorals, biceps, latissimus dorsi, etc.), the four rotator cuff muscles (i.e., supraspinatus, subscapularis, teres minor and infraspinatus) (see Figure 2) are primarily responsible for making sure the end of the arm moves and rotates easily in the glenohumeral joint. Because of their attachments to the arm and shoulder blades, the rotator cuff muscles are intricately involved in nearly every movement of the shoulder and arm. For the same reason, they are also vulnerable to injury and dysfunction from accidents, musculoskeletal imbalances, overuse and/or lifestyle habits.

Figure 2: The rotator cuff muscles (front and back view)

Figure 2: The rotator cuff muscles (front and back view)

What can cause or contribute to a rotator cuff injury?

Each of the rotator cuff muscles originates from the shoulder blade and attaches to various parts of the upper arm. In order for the rotator cuff to work correctly, the shoulder blade needs to remain fairly stable and act as an anchor for these muscles during movements involving the arm. Conversely, the arm must have the ability to rotate freely in the glenohumeral joint so that, when the arm is moving, the shoulder blade does not have to compensate and lose its steady position on the ribcage5. This relationship of stability and mobility is integral to the correct function of the rotator cuff muscles (and shoulder girdle as a whole).

Unfortunately, accidents, daily habits, postures and musculoskeletal compensations can strain the rotator cuff muscles, affecting the stability of the shoulder blade and mobility of the arm in the glenohumeral joint, causing and/or contributing to ongoing pain and dysfunction6.

Accidents

The most common way muscles of the rotator cuff are injured when skiing is by falling on an outstretched arm2. Force from the ground transferring up the outstretched arm to the shoulder can strain or tear the muscles that hold the end of the arm in place (i.e., the rotator cuff muscles). In response to such an injury to the rotator cuff muscles, other muscles around the shoulder (i.e., rhomboids, trapezius, biceps, etc.) typically tighten up to prevent movement of the entire area while the injury heals. Unfortunately, if these compensation patterns continue, these tight muscles lose their ability to stabilise the shoulder blade(s) effectively and pain and dysfunction of the entire shoulder girdle can result7.

Daily habits and musculoskeletal compensations

Repeated and extended time seated at a computer or viewing a television screen typically results in your head jutting forwards of its optimal position and the shoulder blades moving forward on the ribcage and away from the spine7,8. Similarly, carrying a bag on one side of your body, cocking your head to one side to talk on the phone, handedness or musculoskeletal compensations for an imbalance elsewhere in the body can all pull the shoulder blade(s) out of alignment via the muscles that run from the shoulder blade to the thoracic spine, head and neck (e.g., rhomboids, trapezius, levator scapulae). All of these habits can cause or contribute to ongoing rotator cuff problems.

Similarly, activities like typing, texting, gardening, crafts, playing musical instruments and exercising with equipment that requires us to grip handles, is a constant demand on the muscles and fascia that control our hands and wrists. These tissues of the lower arms are interconnected with the muscles and fascia of the upper arms/shoulders. Over time, restrictions in the tissues and muscles of the hands, wrists and forearms can affect the function of the structures in the upper arms and shoulders and limit mobility in the glenohumeral joint, leading to enduring rotator cuff issues9.

What can I do to help?

The key to helping clients overcome rotator cuff injuries is to implement corrective exercise strategies that promote stabilisation of the shoulder blades while gently restoring mobility of the arm in the glenohumeral joint once clearance is obtained from a licensed medical professional. Part of this strategy is to correctly align the thoracic spine, ribcage, neck and head so the bones and muscles that interact with the shoulder blades are in their proper position. Once the shoulder blades are stable, progressive strategies can be implemented to gently mobilise the glenohumeral joint. This two-pronged approach will encourage healing of the muscles of the rotator cuff.

What corrective exercise strategies should I use?

Strengthening exercises can be used to help stabilise the shoulder blades and stretching exercises can be used to help mobilise the arms. However, before introducing any of these types of exercises into a client’s programme, you should perform the self-myofascial release techniques outlined below to ensure myofascial restrictions do not limit potential muscle activation and/or muscle elasticity10.

Corrective exercise strategies for the head and neck

Self-massage technique – Theracane on neck

A forward head position pulls the shoulder blades up and forwards via the trapezius muscles. Similarly, a head and neck position left or right of centre can affect the position of the shoulder blades on one side. A Theracane is a great self-massage tool that can be used to release the muscles of the neck and shoulders to help the scapula settle back into its correct position on the ribcage.

Instruct your client to use the knob on the hook end of the Theracane to apply gentle pressure to any sore spots they find on the back and side of their neck and top of their shoulders. Coach them to use their hand on the bottom handle of the device to push down and out to control the pressure of the massage. Perform for two to three minutes each day on each side.

Note: A Theracane® can be found online for about £20-£30.

Stretching exercise – neck side stretch

Once the neck and shoulder tissues have been loosened up, you can stretch the muscles on the side of the neck. This will help align the head and neck to centre and allow the shoulder blade(s) to drop back into proper alignment.

Instruct your client to sit in a chair and grasp the underside of their seat behind their right buttocks with their right hand. Coach them to pull their right shoulder blade back and down as they use their left hand to pull their left ear towards their left shoulder. Perform stretch on both sides for 10-20 seconds daily. Have clients evaluate which side is tighter and encourage them to stretch the tighter side two to three times more often.

Instruct your client to sit in a chair and grasp the underside of their seat behind their right buttocks with their right hand. Coach them to pull their right shoulder blade back and down as they use their left hand to pull their left ear towards their left shoulder. Perform stretch on both sides for 10-20 seconds daily. Have clients evaluate which side is tighter and encourage them to stretch the tighter side two to three times more often.

Corrective exercise strategies for the thoracic spine

Self-massage technique – tennis ball(s) beside spine and around shoulder blade

When the thoracic spine has a sideways bend in it (i.e., scoliosis) or is excessively rounded forward (i.e., excessive thoracic kyphosis), the muscles that lie beside the spine (i.e., thoracic erector spinae) and the muscles that go from the spine to the shoulder blades (i.e., rhomboids and trapezius) can become tight or restricted and affect the position of the shoulder blade(s). Using a tennis ball to massage these muscles will help allow the shoulder blades to fall back into proper alignment.

Instruct your client to lie on the floor with knees bent and head supported by a pillow. Coach them to use a tennis ball to apply pressure to any sore spots they find on either side of their spine and out to the inner edge of their shoulder blade. As they move out towards the shoulder blade, have them hug their opposite shoulder to increase the pressure. Perform for 15-20 seconds on each sore spot on both sides of the upper back at least once a day.

Strengthening exercise – lying shoulder retraction

Once the muscles of the upper back have been loosened, you can perform an isolated strengthening exercise to help stabilise the shoulder blades and place the heads of the upper arm into their correct position. This exercise is ideal for helping clients learn how to pull their head back and retract/depress their scapula correctly, before progressing to more challenging strengthening exercises using resistance bands and/or weights.

Instruct your client to lie on the floor with knees bent and hands out to their side with palms up. Coach them to lengthen the back of their neck by tucking their chin in and pulling their head back to the ground. If your client cannot make contact with the ground without tipping their head back, provide them with a pillow under their head. With neck lengthened, instruct your client to retract and depress their shoulder blades. As they become proficient at this movement, progress the exercise by instructing them to turn their palms downward (without letting go of the muscles that are retracting and depressing their scapula). Perform three to five times per day, holding each repetition for 10 seconds.

Corrective exercise strategies for the arms and hands

Self-massage technique – front of shoulder and biceps

The biceps muscles originate on the front of the shoulder blade. When these muscles become tight due to overuse from exercise and/or extended periods of computer work, they can restrict movement of the arm in the glenohumeral joint and pull the shoulder blade out of alignment.

Instruct your client to lie face down on the floor and use a tennis ball, baseball or lacrosse ball to massage the front of their shoulder and biceps. Perform once a day on each side for 10-15 seconds on all sore spots.

Instruct your client to lie face down on the floor and use a tennis ball, baseball or lacrosse ball to massage the front of their shoulder and biceps. Perform once a day on each side for 10-15 seconds on all sore spots.

Stretching exercise – biceps stretch

This stretch should be done after the massage techniques detailed above. It will improve flexibility of the biceps, promote mobility of the glenohumeral joint and allow the scapula to sit back and down correctly on the ribcage.

Instruct your client to stand facing away from a high countertop or piece of gym equipment. Coach them to lift their right arm behind them with their thumb pointed downward. Have them pull their right shoulder blade back and down while keeping their right arm rotated to maintain the thumb-down position. Instruct your client to gently rotate their body away from their right arm while keeping their right shoulder blade back and down. Perform this stretch on both sides for 15-20 seconds at least once a day.

Stretching exercise – palm on wall stretch

This stretch should be done once your client has massaged the muscles of their forearm, shoulders and neck (see above). This is a great flexibility exercise that will promote mobility of the arm from the hand all the way up to the glenohumeral joint.

Instruct your client to stand facing a wall, and extend their left arm at shoulder level with their palm flat on the wall and arm straight. Coach them to pull their left shoulder blade back and down and gently turn their right shoulder away from the wall while maintaining the stabilised shoulder blade position on their left side. Progress this exercise by teaching your client to gently try to rotate their left arm forward without bending their arm or moving their palm on the wall. The rotation of the arm should happen at the shoulder, elbow and wrist, not by sliding the palm forward. Perform for 10-20 seconds on both sides at least once a day.

Instruct your client to stand facing a wall, and extend their left arm at shoulder level with their palm flat on the wall and arm straight. Coach them to pull their left shoulder blade back and down and gently turn their right shoulder away from the wall while maintaining the stabilised shoulder blade position on their left side. Progress this exercise by teaching your client to gently try to rotate their left arm forward without bending their arm or moving their palm on the wall. The rotation of the arm should happen at the shoulder, elbow and wrist, not by sliding the palm forward. Perform for 10-20 seconds on both sides at least once a day.

Conclusion

A rotator cuff injury is not only painful but can affect one’s ability to exercise and engage in daily activities. While it is not within your scope of practice to diagnose a client’s rotator cuff injury, you can use your knowledge of what causes or contributes to such a problem to design effective corrective exercises to help.

This article previously featured in the Fitpro digital magazine.

References

- Yamamoto A et al (2010), Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population, Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 116-120.

- Kocher M & Feagin A (1996), Shoulder injuries during alpine skiing, American Journal of Sports Medicine, 24(5): 665-9.

- American Council on Exercise (2010), ACE Personal Trainer Manual (4th Edition), American Council on Exercise.

- Gray H (1995), Gray’s Anatomy, New York: Barnes & Noble Books.

- Cook, Gray (2010), Movement, Aptos, CA: On Target Publications.

- Price J & Bratcher M (2019), The BioMechanics Method Corrective Exercise Specialist Certification Program (2nd Edition), The BioMechanics Press.

- Price J (2018), The BioMechanics Method for Corrective Exercise, Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Kendall F, McCreary E & Provance P (1993), Muscles; Testing and Function (4th Edition), Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkens.

- Myers T (2001), Anatomy Trains. Myofascial Meridians for Manual and Movement Therapists, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- Rolf IP (1989), Rolfing: Reestablishing the Natural Alignment and Structural Integration of the Human Body for Vitality and Well-Being (revised edition), Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press.