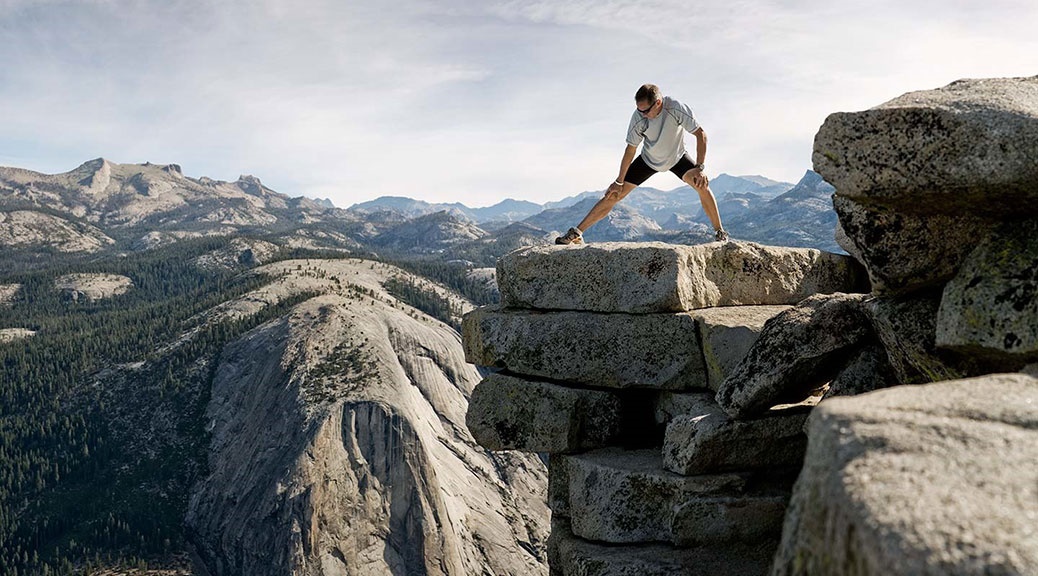

Meet the man who lives life on the edge. Olivia Hubbard speaks to Charlie Engle and feels in awe of his running hunger, human endurance and courageous attitude to life’s challenges.

Now I’m no running fanatic – far from it – but I do appreciate the fast-moving pace at which my body demands to be flung. The initial burst of eager power, the mid-way shortness of breath and the unannounced sprint finale – think misplaced footwork and raging endorphins searching for the finish. I could say that I was addicted – I long for the post-run sensation that clears the mind and awakens the limbs – but then I spoke to Charlie Engle and addiction was defined.

Pages to recall one’s life

Engle is speaking to me from North Carolina. He has set aside two hours of running for that day and his philosophy fascinates me – it’s as blunt as it comes: “Run as hard as f*****g possible.” He then goes on to say, “Allow your body to go through the cycles that it’s going to go through naturally. Time is usually the biggest problem people have; you can allocate your time and then you have no excuse not to go out there and do something.”

After a decade-long addiction to crack cocaine and alcohol, Engle hit rock bottom with a near-fatal six-day binge that ended in a hail of bullets. As Engle got sober, he turned to running, which became his lifeline, his pastime and his salvation. His book, Running Man, is an incredibly raw account of Engle’s life story. What Engle achieves in prison and how he copes mentally is beyond my comprehension. When I asked him about writing Running Man he said, “I would much rather run across the Sahara desert again than write that book.”

Olivia Hubbard: What is it about long distances that gets you pumped?

Charlie Engle: I’ve always enjoyed it. I enjoy putting my toe on the starting line and trying to do my best – that’s why I say half marathons and marathons are some of the hardest races. You measure yourself against everyone else. The beauty of ultras is that time is rarely a factor; time is not nearly as important. You’ll find your way to ultras eventually, Olivia!

OH: You’re pals with American author and journalist Christopher McDougall?

CE: Born to Run hit a nerve and it landed at a perfect time. It spurred on the barefoot running craze and a new interest in ultra running. I have had a couple of knee surgeries in my life and my orthopaedic jokes that Born to Run paid for his house at the beach because so many runners became injured and needed repairing. I believe that barefoot running is a good thing for those who grow up running; for the rest of us, it takes patience.

Running the Sahara

OH: At the beginning of November 2006, you were preparing to run two marathons every single day. Little did you know you would do this without a day off for 111 days, along with runner companions Ray and Kevin. How did you prepare?

CE: We had no training manuals or ‘guides for dummies’ to give us tips. Kevin, Ray and I had to devise our own plans. I knew we were not training to get faster; we were training to stay healthy under extreme duress. I logged about 100 miles a week, lifted weights and did yoga to balance my fitness.

OH: What caused your fears in the desert?

CE: Everything from running out of food and water to getting lost and having injuries and illness. Even though we had a doctor with us, people were sick – sometimes they were very sick. There was nowhere to go. No aeroplanes, no nothing. If you had to escape the desert, it would take at least four or five days to get out from almost any point.

There is also the fear of failure and embarrassment because some of the things I’ve chosen to do, I’ve chosen to do very publically and the necessity of that is so that the project can be funded. I could never have managed to pull off the Sahara desert project without [actor] Matt Damon – without his production company. What goes along with that is, “What if I’m the guy who fails? What if I get injured and I can’t continue?” Matt Damon was humble and generous with praise. He’s just a good guy and wants to do good in the world. We co-founded H20 Africa and raised six million dollars for clean water projects in Africa. Today, Matt is partnered with water.org, which is run by a friend of mine. It is the true legacy of the documentary.

OH: What was the funniest moment in the Sahara?

CE: This is actually quite harrowing for me. So, early on in the first few days, there were a couple of goats along with us. I actually became friends with one of the goats so, by day four of the Sahara run, I went around the side of the truck and tried to pet my friend and the goat’s not there. I go and ask Mohammad, “What happened to Simone?” He looks at me and then says, “Did you enjoy your dinner last night?” I said, “Yeah.” He replied, “You can thank Simone.” I’m vegetarian and nutritionists at Gatorade told us to consume about 10,000 calories a day. I forced as much food into my stomach as possible; I hated starting out on a full belly but knew I had to get used to it and had to accept that I needed to consume meat.

OH: What were your backpack essentials for the Sahara?

CE: Peanut butter! Nutella! Before the Sahara I had never had Nutella before; I don’t know why it was available in the desert. [Charlie’s wife yells in the background, “Because it never goes bad!”] Butter! Every single day I ate an entire stick of butter. They made their own butter in the Sahara from camel’s milk and goat’s milk, so butter was plentiful. I don’t even eat butter – so much fat! That was an essential. My iPod and photographs of loved ones, too.

OH: “We had all been strong, all been weak, now I wanted the team to be empty.” What did you mean by that?

CE: It goes back to wanting pain – the only way for me to empty myself and the craziness and the internal chaos and the rest of it that comes from every-day normal life. Running across a place like the Sahara, where we had no electronics, every day was filled with simplicity. I needed to put one foot in front of the other and run. By having that single focus, I had to deal with a lot of stuff out there. Every one of those things that I dealt with was towards the same goal. This was to get us to Egypt and the Red Sea. So I ran and ran until I couldn’t run any more. I encouraged my teammates to run until they couldn’t run any more. When we got to Egypt and we picked up the pace, I knew we hadn’t emptied ourselves out yet – I do look at it like a vessel. I wanted to pour every drop into what I’d brought to the Sahara and I wanted to refill it with hopefully something better: new lessons, more confidence, a better understanding of who I am and of the people I was with.

Everyone trains for races – the goal is to train well enough to make the race easier or to maximise your effort and I’ve always said that’s actually a mistake in a way because the goal is to get yourself in a position where you can run as hard as you can, to actually reach that place in the run where you want to quit. You need to pull yourself back from that, because there are no better lessons than the ones we learn when we want to quit. Sometimes you learn the lessons from quitting. All of us have quit something at some point and regretted it and that’s part of life.

There, at the end of the Sahara, I didn’t want to finish that run and think to myself, “We could have gone a little faster.” I can honestly say that, at the end of that run, as a team we left every ounce of energy and knowledge and all that we were out there in the desert. From that point forward, all three have been busy using what we learned there in our lives.

OH: Following the Sahara mission, your fame led to an investigation and a subsequent unjust conviction for mortgage fraud, whereby you spent 16 months in federal prison in Beckley, West Virginia. While in jail, you pounded the quarter-mile prison track and soon your fellow inmates were joining you. In prison, you said you missed “the beautiful struggle of running”. Tell me about your relationship with pain and your running experience in prison.

CE: I do believe that, for me and for most people, we’re not capable of learning very much from the things that are easy. And, for me, running after I became sober became the mechanism where I could tap into pain at pretty much any time. Alcohol and drugs masked everything, both good and bad. If I was happy, I drank. If I was sad or angry, I drank. Hell, if I was breathing, I drank! It didn’t just consume my time, it consumed my spirit. Running does the exact opposite. Running makes me real. Running highlights whatever feelings I am having and makes them exponentially greater. Mostly, running actually allows me to identify what I am feeling. That never happened when I drank or used. Of course, when I stopped running, I was still in prison. So I don’t know if running in prison changed me but it definitely saved me.

In prison, I could transport myself to that place where I could force struggle upon myself and, rather than shy away from it, I welcomed it and I loved to put myself in that position. Out here in the greater world, you can find ways to feed that need for exercise or stimulation. In prison, there really was no stimulation that wasn’t self-generated and that’s the big difference. I was in hell [laughs] but not so much how people might see it on a prison television show. It wasn’t about being fearful – just losing my mind.

OH: And “to keep your sanity, you did the insane?”

CE: There is something about the harshness of the Badwater ultra race and the starkness of it. You have to be in the right mindset to find the beauty in that valley. In prison, there is something very relatable to that. There was no beauty there; I had to find the beauty myself and the only way I could really do that was in my mind. I knew the Badwater course so intimately and I knew the people understood the experience so deeply that it allowed me to transport myself there mentally and [it was] almost like a running meditation. I had calculated the distance; it meant doing 540 laps for 24 hours in total over two days on the prison track. When we were in lockdown, I was the fool pounding out miles on the hard floor next to my bunk. An inmate said to me, “You don’t belong in prison mate; you belong in a f*****g insane asylum.” I got the nickname of Running Man; they didn’t know how well it fit me.

OH: Tell me about the running group in prison.

CE: When I got to prison, there were a few runners here and there but no one knew what they were doing! Think about it –they’re in prison because they sold drugs or they did drugs. So we’re not talking about people who grew up running track in high school or doing their local 5k. They’re in this place that is full of deprivation and what I found in prison is that, if I just went out there and ran around the track, people would stop me or find me later and ask me questions about running. In prison, it’s rare that people will do something for nothing. What I learned in addiction recovery a long time ago was that to keep it, you have to give it away. So my love of running is so deep and I think that the gift of running and of physical exertion is so important to everybody that it was certainly something I was willing to share.

OH: How did you coach fellow inmates?

CE: It’s hard for the average person to imagine everything in your life being gone tomorrow. You may still have a loved one but you don’t have access to them. Your time is not your own. You’ve lost control of everything. That’s prison. Running is such a cathartic gift; it allowed me to find the one thing that was so comforting but opened up a whole new world. I do know that at least a dozen people who I worked with in prison are still runners today now they’re out of prison. If I did any good in there, I would have to rank that up as maybe the best thing.

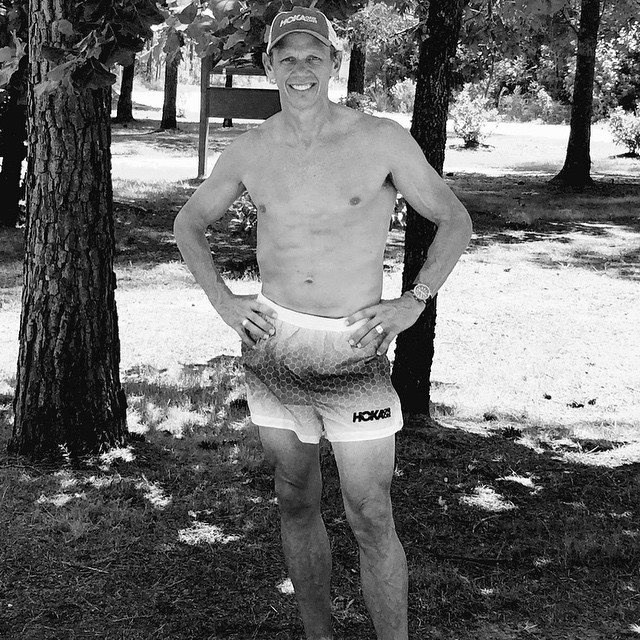

OH: One for the running nerds: best running shoe?

CE: I’m a HOKA guy. Have been for years. The Stinson has saved my running career in a way because the super cushioning helped me after a lot of years of running. I recover a lot more quickly. I can run downhill fast and I can do things that without the cushioning in other shoes I’ve never been able to do. I’m a happy HOKA runner.

OH: What’s your scariest moment of any running experience?

CE: In a race called the Southern Traverse in New Zealand, I got ‘clipped out’ one time. That means that I had gone up and over a mountain pass and was headed down the other side. It was very treacherous going down and, if I fell, it would mean death or severe injury. About halfway down, I realised I had come to a massive cliff wall and couldn’t go any further. It was getting dark so also impossible to climb back up. I was stuck. And, as I would find out later, I was on the wrong mountain! So nobody was looking for me. I put a stake in the ground and strapped myself to it for the night. In the morning, I had no choice but to risk climbing up again. I was holding on to tiny plants and loose rocks; I thought for sure I would fall. But adrenaline and fear are potent motivators and I made it back to the top and back to the course. If a person races in enough very long events, it is only a matter of time before they have a similar experience. But, frankly, I loved it. That feeling of being on the edge is magnificent.

OH: What quote do you live by?

CE: “Never let your best day or your worst day rule your emotions. Real life is lived in the middle ground.” I have no idea if I made that up or if I heard it elsewhere. Someone else has likely said it better than that but I believe it to be true.

OH: When are you at your most happiest?

CE: I am at my absolute happiest when I’m at my most uncertain about my ability to actually complete what’s in front of me. At marathons, there will be people who have run 50 marathons, 100 marathons and I’ll ask them – the race is tomorrow morning – whether they have any doubt that they’re going to finish the race. And they will say, “No.” My answer to that is, “Don’t you miss being unsure?” Because I love the feeling of standing on the starting line and wondering if I can actually do this.

OH: Finally, do you think you’re too hard on yourself and when will you ‘pat yourself on the back’ for what you have achieved?

CE: I do, yes, and I think that realisation has only come with age. My wife reminds me not to be so hard on myself. It’s part of my addiction. It was why prison was so hard. Not being able to run and not being able to go to a recovery meeting and talk to people who are like me left me with no outlet at all. The same thing happened in the Sahara to a degree. Yes, I had running, but I had no one else out there for months who was really relatable on the deepest level. As I have gotten older, I really do have a greater appreciation for any accomplishment. I don’t know if I pat myself on the back but I certainly try to be grateful. The conundrum is this: if I have gone on a true journey of self-discovery, then I learn something each time I go out and try a new thing. In turn, that new discovery makes me want to keep going. This makes being satisfied pretty difficult. As long as there are still new corners of the world to see and new parts of me to find, I expect I will keep running.

OH: Running Man captures the harsh realities of poverty, human strength, addiction, teamwork, family and self-imposed pressures. I just hope Engle ‘pats himself on the back’ one of these days because he definitely deserves it. I found him to be a decent bloke with no pretence who is incredibly humble. Running Man is out on 8 September. RRP £16.99