Kevin Murray explains how the nervous system is implicated in pain and how you can help clients to better understand their pain and, as a result, exercise in a less fearful way.

Encountering danger is a normal part of life and the brain is command central for detection, evaluation and organisation of how an individual responds to it1. To the chronic pain client, pain is often interpreted as something threatening – a signal of potential harm to their overall safety and wellbeing2.

So, when pain emerges, how is the nervous system implicated? When clients become avoidant and fearful of everyday movements, how can fitness professionals help them navigate their movement limitations in conjunction with their emotional, psychological and social stressors?

Neurophysiological structure and function: The accelerator and the brake

The accelerator: The human brain is organised hierarchically and develops primarily from the bottom up3. As neural networks emerge and evolve, they are governed through the interplay of time, genetics and environmental interaction.

The limbic system is one of the first to ‘come online’ and is shaped in direct response to experience: in partnership with one’s biological and genetic make-up1. Composed of the thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala and other subcortical structures, this system is deeply rooted in emotion and acts as the ‘emotional hub’ for all vertebrates.

Along with the brain stem, the limbic system functions similar to a smoke detector. It’s on the lookout for potential threats and rewards, and is the evaluator of emotional relevance1.

Emotions come fully equipped with turbochargers and the limbic system is the accelerator. Input from the eyes, ears, nose and somatosensory systems all have first dibs on interpreting incoming information. Left to its intuitive presumptions, the limbic system can run one’s smoke detector into overdrive, becoming hyper-alert and overly responsive.

In these instances, a steadfast braking system is required.

The brakes: Juxtaposing the limbic system is the pre-frontal cortex (located in the frontal lobe). This system is last to fully mature and is responsible for higher executive functioning3. Commonly referred to as the rational brain, the pre-frontal cortex is at the helm of functions such as anticipation and feed-forward planning, emotional regulation, empathetic understanding, decision making and problem solving1.

With the limbic system operating as a perceptual smoke detector, the pre-frontal cortex functions more like a watchtower, cognitively analysing and evaluating circumstance from the top down. It’s far less likely to jump to hasty assumptions. Instead, introspection and reasoning are this system’s modus operandi.

For instance, observing an individual walking down a dimly lit street wearing a business suit likely wouldn’t set off many alarm bells. The limbic and pre-frontal regions assess the situation and come to an agreement: ‘nothing threatening here’. However, spotting that same silhouette dressed as a clown with full make-up would surely precipitate a reaction from one’s smoke detector. The conspicuous, sinister nature of a clown is salient enough to facilitate both a bottom-up (limbic system) and top-down (pre-frontal cortex) response. Both the smoke detector and watchtower are in total unison: ‘this is potentially threatening to us and our safety’.

But what happens when limbic and pre-frontal appraisals perceive otherwise benign or neutral input as salient, threatening and potentially harmful? How does pain influence these two regions?

The nervous system and chronic pain

Nothing has the element of pain. Not a hammer, not a knife, not even the coffee table that’s become a magnet for stubbing toes. Nothing has the element of pain except that which the brain perceives as being painful.4 In other words, pain is an emergent property of the brain, influenced by neurobiological, cognitive, sensory and affective inputs.

And, because pain relies on context, the nervous system is on a continuous exploration of all available information to assess the cause of pain, so it can be avoided in the future. Left alone to its immediate, jumping-to-conclusion mechanisms, the smoke detector is often first to be triggered, increasing hyper-arousal, movement hyper-vigilance and fear-avoidance tendencies.

In these instances, the smoke detector and watchtower are no longer operating as an adaptive, unified alliance. Approaching one and not the other is therefore an incomplete strategy.

Approaching pain from the top down and bottom up

Knowing how to influence the limbic and pre-frontal regions is a non-negotiable when working with clients in pain.

Merging both into an exercise strategy involves recalibrating the smoke detector’s threat appraisals and strengthening the watchtower’s capacity to regulate emotions while simultaneously monitoring internal bodily sensations, referred to as interoception1.

Top down

How can health and exercise professionals approach pain from the top down? Through a two-phase process: both taking place through the medium of consultation.

Remember, the pre-frontal cortex is involved with cognitive undertakings such as regulating emotions, planning and anticipation, analytical appraisal, problem solving and decision making.

As such, enquiries into the client’s point of view foster empathy, mutual trust/rapport and the inception of safety. As this develops, the restoration of agency (the ability to have influence over one’s circumstance/feeling in control of one’s life) can begin.

The following questions emphasise each client’s unique point of view regarding their pain experience and are designed to magnify cognitive understanding and enhance emotional awareness. The answers can be profoundly influential for client and practitioner.

- “What sorts of things have you been told about pain and what it means?”

- “What specifically have you missed out on because of chronic pain?”

- “How will you know that working together has been a success?”

- “Do you have a sense of what you’ll reclaim once chronic pain is no longer a central theme in your day?”

Here are some additional enquiries with top-down relevance:

- “Is there something you know now that you didn’t know before our session began?”

- “How do you see me contributing to your journey towards reducing pain?

- “What will be different when pain is no longer as it is today?”

- “If you could envision a future where pain is no longer present, what do you imagine being possible?”

- “If we could fast forward to a future timeline without pain, what will you be most proud of about your commitment to yourself?”

In phase two of the consultation, the focus is aimed at educating clients on the most up-to-date literature on pain science and emphasising a conceptual change from ‘pain is a sign of damage’ to ‘pain is a protective mechanism’4. This is central in helping clients ‘make sense’ of their pain experience.

Imagine a client’s sense of assurance (and emotional relief) when they realise pain is a ‘protective mechanism’ as opposed to a ‘definitive sign of tissue damage or serious injury’. Emotions, perceptions, appraisals, thoughts, beliefs … they all have an opportunity to expand and evolve through education.

However, as influential as a top-down approach is, the consultation alone is not enough. Cognitive understanding does not change how one feels as they move. Integrating the limbic system is still paramount.

Bottom up

When the smoke detector’s alarm bells begin signalling danger, no amount of talk therapy, verbal coaching or logical insight alone will silence them. The moment one detects danger, ‘fight or flight mode’ occurs1.

Remember, the limbic system is shaped in direct response to experience. Therefore, if a client has multiple reference points reinforcing that movement equals pain, finding novel strategies that help clients learn to regulate autonomic arousal while simultaneously establishing a baseline of pain-free movement is key.

One of the foremost objectives in a bottom-up strategy is enhancing a client’s general sense of safety within their own body1. And, while there is no gold standard departure point, regulating sympathetic/parasympathetic functioning of the autonomic nervous system is an excellent bottom-up starting point.

Breathing is one of the few functions that is influenced by both cognitive and autonomic control5. Inhalations engage the sympathetic nervous system, resulting in an increased heart rate, while exhalations stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), slowing one’s heart rate.

When functioning optimally, rhythmical heart rate fluctuations between the SNS and PNS (referred to as heart rate variability) enhance one’s control over impulsive emotions6. In fact, around 80% of the vagus nerve fibres (connecting the brain to many internal bodily organs) are afferent fibres, meaning they travel from body to brain1.

Therefore, deliberately focusing on breathing acts as a communication highway between the body and the nervous system. As such, this bottom-up strategy helps clients learn to regulate physiological arousal while recalibrating their limbic system’s response to threat appraisals before any corrective intervention takes place.

Bottom-up practical application: Breathing

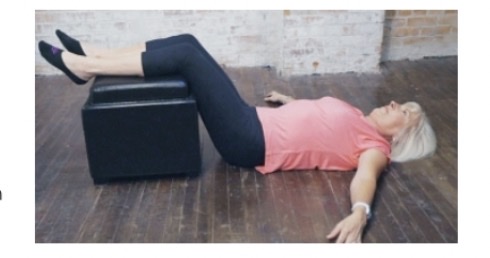

In this context, the purpose of the client lying supine in the 90/90 position is to create a stable base of support (perpendicular to gravity’s vector) where clients can successfully learn to rhythmically engage their diaphragm independent of gravitational perturbations.

Taking into account neurophysiological and psychosocial considerations, this exercise aids in moving clients towards the following objectives:

- Down-regulating heightened states of fear, apprehension and reflexive guarding

- Enhancing interoception

- Fostering the emergence of emotional regulation skills

- Upregulating credible evidence of safety within one’s own body

- Cultivating an increase in somatosensory awareness

- Amplifying emotional resiliency and expanding tolerance for approaching novel experiences

- Re-establishing the client’s agency over their environment/circumstance

- Learning how to differentiate various bodily sensations and uncoupling associative-coherent narratives that movement equates to hurt/harm

Top-down and bottom-up integration

Practical application: Graded exposure

Gradually exposing a client’s nervous system to novel movements that scale in biopsychosocial complexity is referred to as graded exposure7. This approach provides an associative re-learning opportunity where the limbic system and pre-frontal cortex learn and adapt in response to a new experience – the essence of neural plasticity.

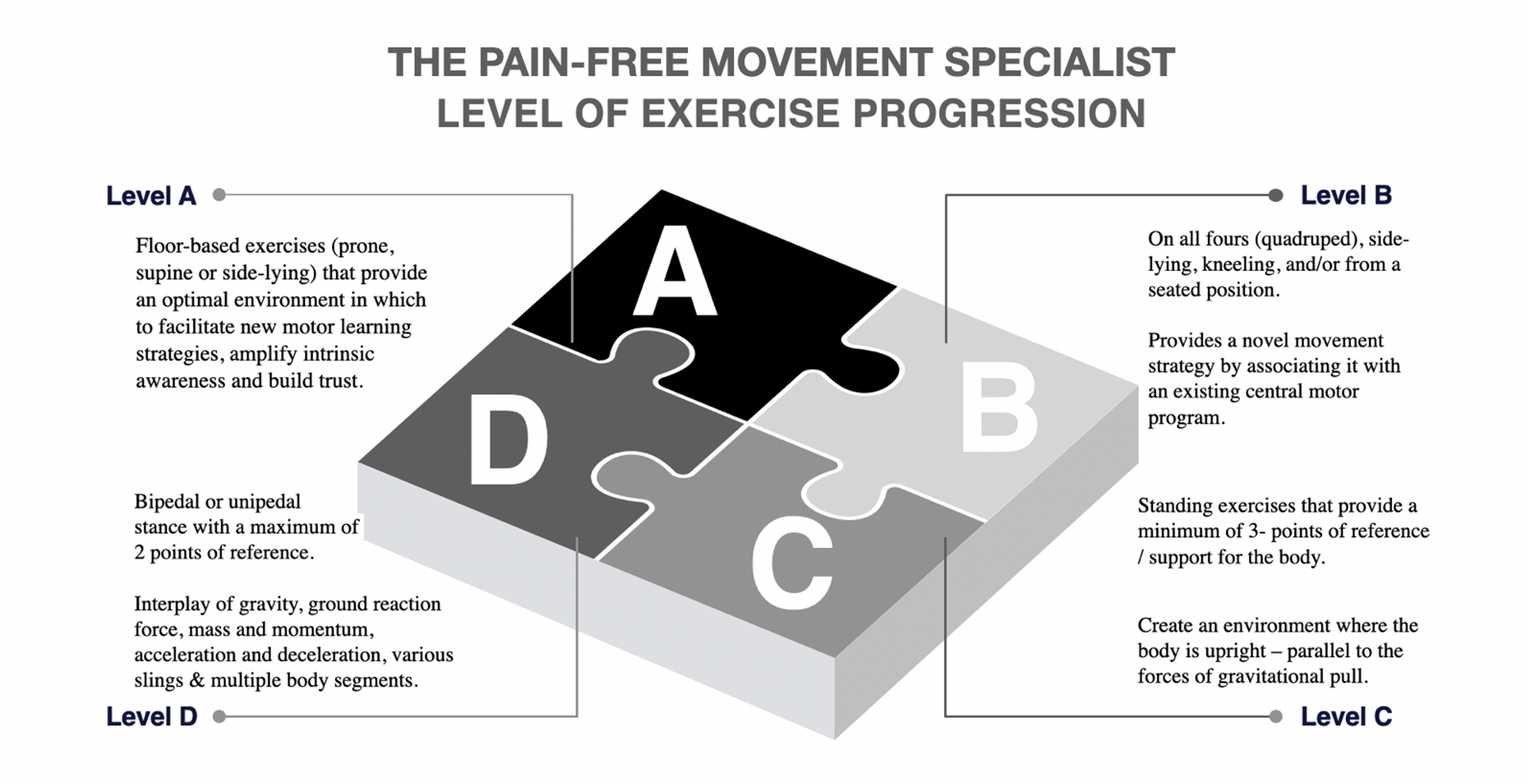

The following is a system for categorising corrective exercises from a graded exposure perspective. Each ‘level of exercise’ builds off the previous and centres on a biomechanical and neurophysiological continuum which gradually exposes clients to their subjective fears and anxieties.

This framework fortifies re-establishing adaptive appraisals and communication between the smoke detector and the watchtower within the context of movement. For instance, if a primary objective in your corrective exercise strategy is to enhance thoracic extension, Function First’s ‘Level of Exercise’ continuum serves as a graded exposure framework for neuro-physiological and biomechanical exercise progressions.

This framework fortifies re-establishing adaptive appraisals and communication between the smoke detector and the watchtower within the context of movement. For instance, if a primary objective in your corrective exercise strategy is to enhance thoracic extension, Function First’s ‘Level of Exercise’ continuum serves as a graded exposure framework for neuro-physiological and biomechanical exercise progressions.

The exercise sequence below demonstrates a progression though the exercise continuum, with exercise descriptions highlighting the progression criteria.

Level A corrective exercises

Level A exercises are floor-based exercises (prone or supine) that provide an optimal environment to facilitate new motor learning strategies. This level fosters a down-regulation of the limbic system, helping clients regulate autonomic arousal while enhancing their intrinsic awareness and general sense of safety within the context of movement.

Level B corrective exercises

Level B exercises are performed side lying, half kneeing, kneeling on all fours (quadruped) and/or in a seated position. The ascending complexity here is designed to increase a client’s emotional resiliency towards exercise uncertainty and aid in recalibrating limbic and pre-frontal appraisals.

Level C corrective exercises

Level C exercises are standing exercises that provide at least three points of reference for the body, where the body is upright – parallel to the forces of gravitational pull. These exercises provide an environment where the biomechanical progressions create a reinforcing feedback loop of physiological excitation and modulation, further regulating sympathetic/parasympathetic function and enhancing the re-emergence of efficacy/movement confidence.

Level D corrective exercises

Level D exercises are performed in a bipedal or unipedal stance with a maximum of two points of reference. These exercises are designed for the continuation of cortical (pre-frontal) and subcortical (limbic) integration while escalating in sensory-motor complexity, involving the interplay of gravity, ground reaction force, mass/momentum, acceleration and deceleration, various slings and multiple body segments.

Psycho-social considerations

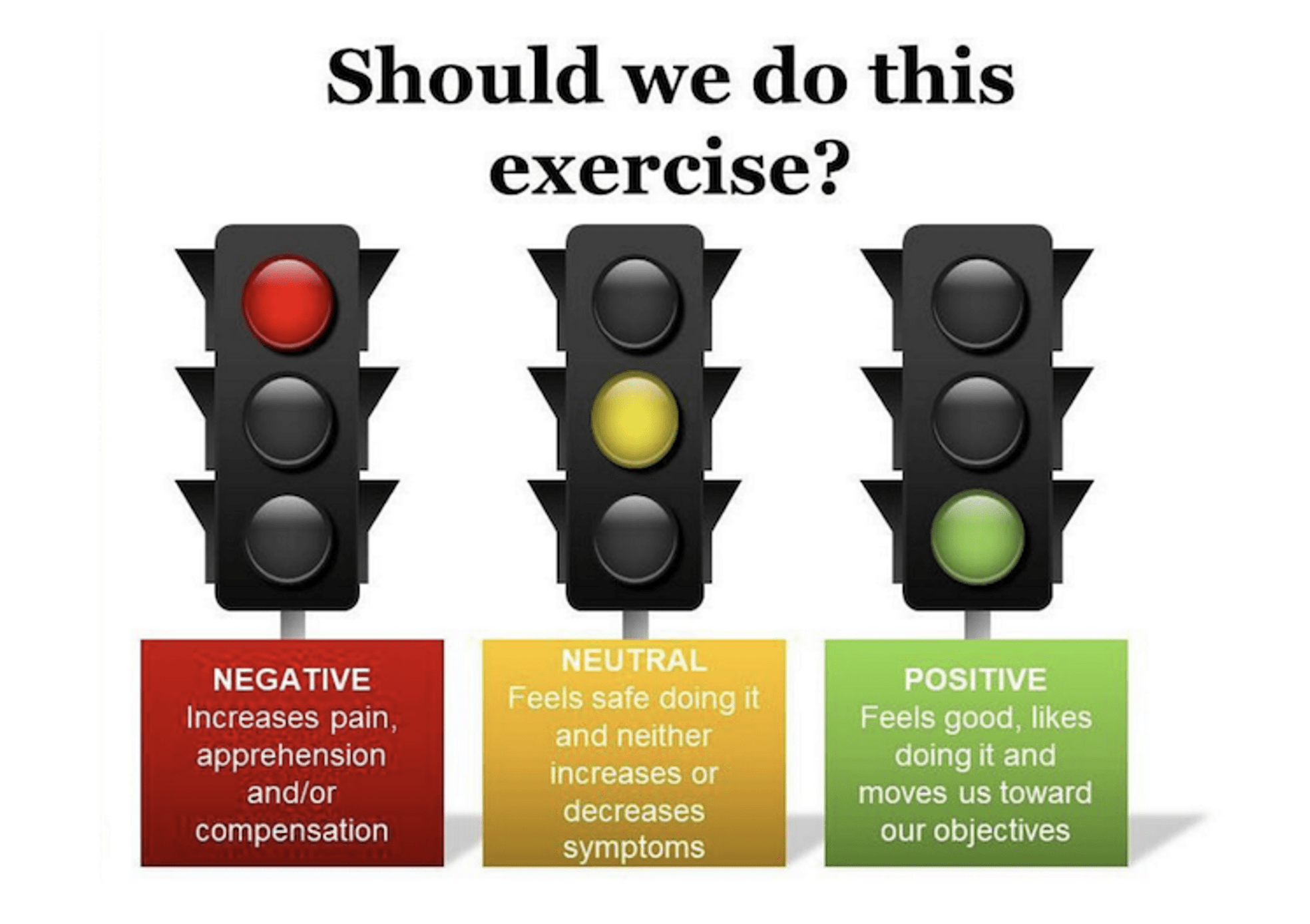

To further bolster each client’s sense of agency, autonomy and self-reliance, the image below takes into consideration each client’s experiential interpretations, which are designed to help:

- magnify the re-education of movement tolerance based on the individual’s own intrinsic awareness

- increase each client’s overall sense of safety and autonomy within the context of movement

- enhance adaptive communication/appraisals between the limbic system and pre-frontal region.

Conclusion

As health and exercise professionals, helping clients with their pain is no easy task. With numerous factors to consider, coupled with the singularity of each individual pain experience, one thing is for certain: there is no universal template applicable to all clients.

Helping clients in pain carries with it an inherent degree of uncertainty. This is inescapable. As such, embracing the ambiguity with a multifaceted and comprehensive strategy becomes magnified.

Taken together, approaching pain from both the top down and bottom up yields a comprehensive and integrated neurophysiological framework which aids in expanding each client’s capacity to regulate emotional, psychological and environmental factors within the context of their movement and pain experience.

Want to learn more from Kevin? Check out these two incredible educations from Kevin and Anthony Carey…