There are many different types of injury affecting the shoulder, but for the purposes of this article, chartered physiotherapists Anna Higo and Nicola Francis will focus on subacromial impingement, which is one of the most common causes of shoulder pain.

Introduction

As physiotherapists, shoulder injuries are a common complaint within the clinical setting. Other shoulder conditions that therapists need to be aware of include:

- Traumatic instability/capsulolabral pathology

- Atraumatic instability

- Rotator cuff tear

- Acromioclavicular joint disease

- Frozen shoulder

- Glenohumeral joint arthritis

- Suprascapular nerve entrapment

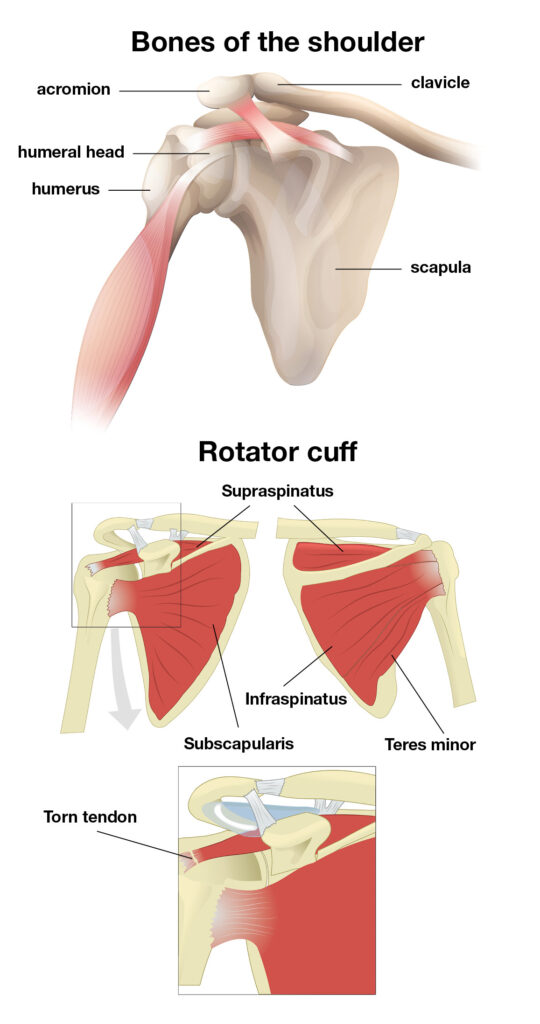

Anatomy

The shoulder comprises a ball and socket joint and has the greatest range of movement of any other joint in the body. Shoulder joint stability is compromised by the fact that the socket, or glenoid fossa, is very shallow. It therefore gains much of its stability through the surrounding soft tissue structures – complex ligaments and muscles. There are four muscles that aid with this stability and they are commonly known as the rotator cuff – subscapularis, infraspinatus, teres minor, and supraspinatus. These four muscles provide dynamic stability to maintain the humeral head within the gleniod fossa. They precisely centre the humeral head by compressing it into the glenoid concavity. The individual muscles of the cuff help to maintain strength in different movement patterns. Supraspinatus in elevation, subscapularis in internal rotation, and infraspinatus and teres minor in external rotation. Thus, as the function of the cuff is primarily a stabiliser of the shoulder, any dysfunction will lead to instability. When the humeral head is no longer stabilised in the glenoid cavity, contraction of the deltoid muscle is ineffective in elevating the arm away from the side, leading to pseudoparalysis of the shoulder.

Subacromial impingement

What is it? It is the most common cause of shoulder pain, resulting in functional loss and disability of the shoulder. The exact pathophysiology of impingement is not completely clear, but Masood et al defined it as symptomatic irritation of the rotator cuff and subacromial bursa within the subacromial space. The subacromial space being defined by the humeral head inferiorly, the anterior edge and under-surface of the anterior third of the acromion, coracoacromial ligament and the acromioclavicular joint superiorly.

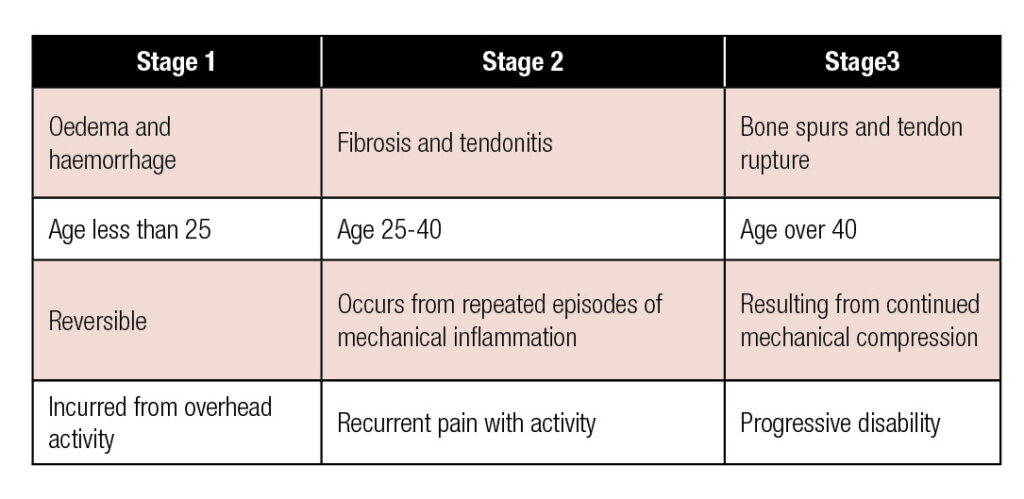

In 1972, Neer formulated that the tendons of the rotator cuff became compressed due to narrowing of the subacromial space. He described these three stages:

Causative factors

It is widely documented that there are two types of impingement, namely primary and secondary.

Primary impingement:

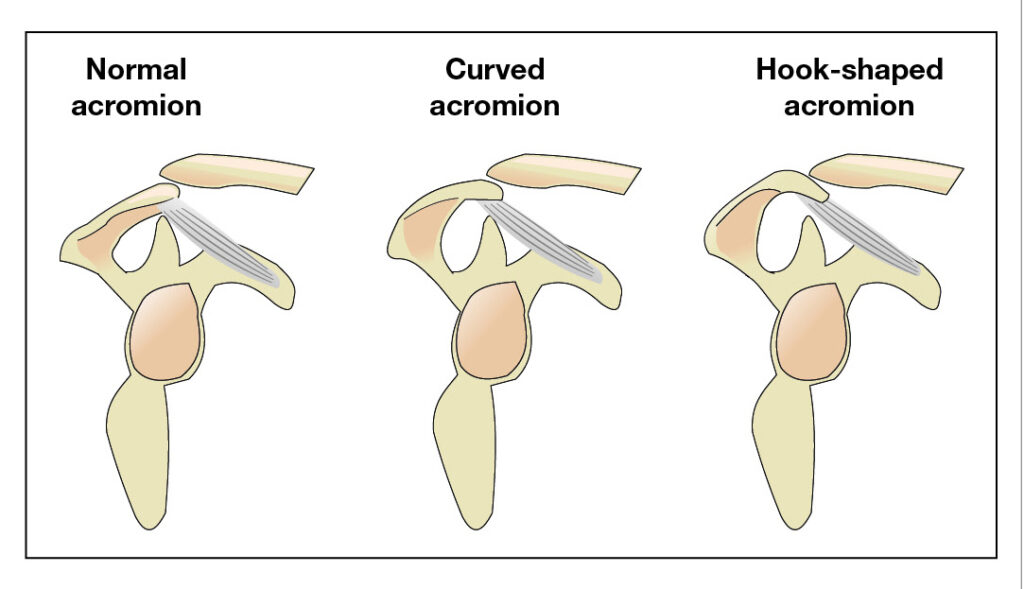

This is usually due to bony abnormalities in the shape of the acromion, congenital abnormalities, and degenerative changes with the growth of bony spurs. In 1986, Bigliani et al classified the acromion into three types, as follows:

Secondary impingement:

Secondary impingement:

This occurs as a result of other problems, such as:

Posture – in a society where we adopt a mainly flexed posture, our shoulder complex is put into forward positions causing undue stresses on the surrounding structures

Repetitive strain/overuse injuries – repeated movements of the shoulder into positions that compress the tendons, i.e., overhead or behind your back

Overload – common in athletes that are either lifting weights or performing overhead activities

Following trauma – direct fall onto the arm can cause inflammation of the bursa and/or tendons of the rotator cuff

Bursitis – the fluid-filled sac that sits between tendons and bones and can become inflamed due to compression

Muscle imbalances

Symptoms of subacromial impingement

Patients with subacromial impingement will describe difficulty lying on that side. There will be an insidious onset of shoulder pain over a period of weeks or months, and the pain will be normally localised over the tip of the shoulder. Any radiation of pain will be lateral reaching to the elbow. The patient will describe pain when lifting the arm out to the side or reaching behind the back.

How is subacromial impingement diagnosed?

Patients with subacromial impingement will have a ‘painful arc’ of shoulder abduction from 60 to 120 degrees. Passive movements should be clear; however, in chronic cases, capsular tightness can develop and lead to stiffness. The position of the scapula is also important. ‘Winging’ scapula may be noted in patients with impingement syndromes, where the medial border of the scapula may be prominent at rest and during arm lowering in order to avoid the passing of the rotator cuff tendon underneath the acromion.

There are various ‘special’ tests for shoulder impingement that can be performed by a chartered physiotherapist. These are carried out to identify which rotator cuff muscles may be affected.

Imaging – further investigations

Be mindful of the client that does not get better through conservative management or becomes worse. Scans may be required to rule out rotator cuff tears or calcification:

- X-ray

- USS

- MRI

Treatment

Conservative

Studies have shown that conservative management of subacromial syndrome resolves the problem in 70-90% of patients. A comprehensive, structured and supervised rehabilitation programme should be the first line of treatment in subacromial impingement syndrome.

A systemic review published in Manual Therapy supports the use of rotator cuff strengthening and stretching as an effective treatment for subacromial impingement. A strong and competent rotator cuff provides the stability that the shoulder, with its extreme range of movement, demands. Exercises that work into internal or external rotation of the glenohumeral joint will target the rotator cuff and therefore improve stability. Other areas to be targeted are scapular stability, thoracic mobility and core.

About the authors

Anna Higo is a chartered physiotherapist with a keen interest in the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of shoulder injuries. She is joint partner of Physiocure (www.physiocure.org.uk) based in North Leeds.

Nicola Francis is a chartered physiotherapist. She works at Physiocure, North Leeds. She has more than 20 years’ experience assessing and treating musculoskeletal and sporting injuries, especially in runners.