Basic alternate leg bounding is a foundational exercise for developing unilateral power for speed training. Here, Derek Hansen and Steve Kennelly for Human Kinetics share some bounding movements.

What is bounding?

Bounding is the adaptations created to increase stride length and overall hip extension power for single-leg jumps. You can incorporate bounding variations into a training programme to develop specific characteristics that improve performance and overall athleticism. Distances of 20 to 40 metres are commonly used for bounding sets, depending on individual circumstances. Include adequate recovery between sets to preserve the quality of work through a training session.

-

Straight-leg bound

Execution

- Stand with feet hip-width apart. Initiate the first bound by sweeping the lead leg forward with the knee joint fully extended. The opposite arm sweeps forward to match the range of the lead leg.

- Quickly draw the lead leg back toward the ground with the foot dorsiflexed to prepare for a dynamic landing.

- Aim for a midfoot ground contact and a tall posture on landing with minimal knee flexion.

- Drive the knee of the free leg forward to initiate the second straight-leg bound and continue with this cyclical bounding movement for 10 to 20 metres.

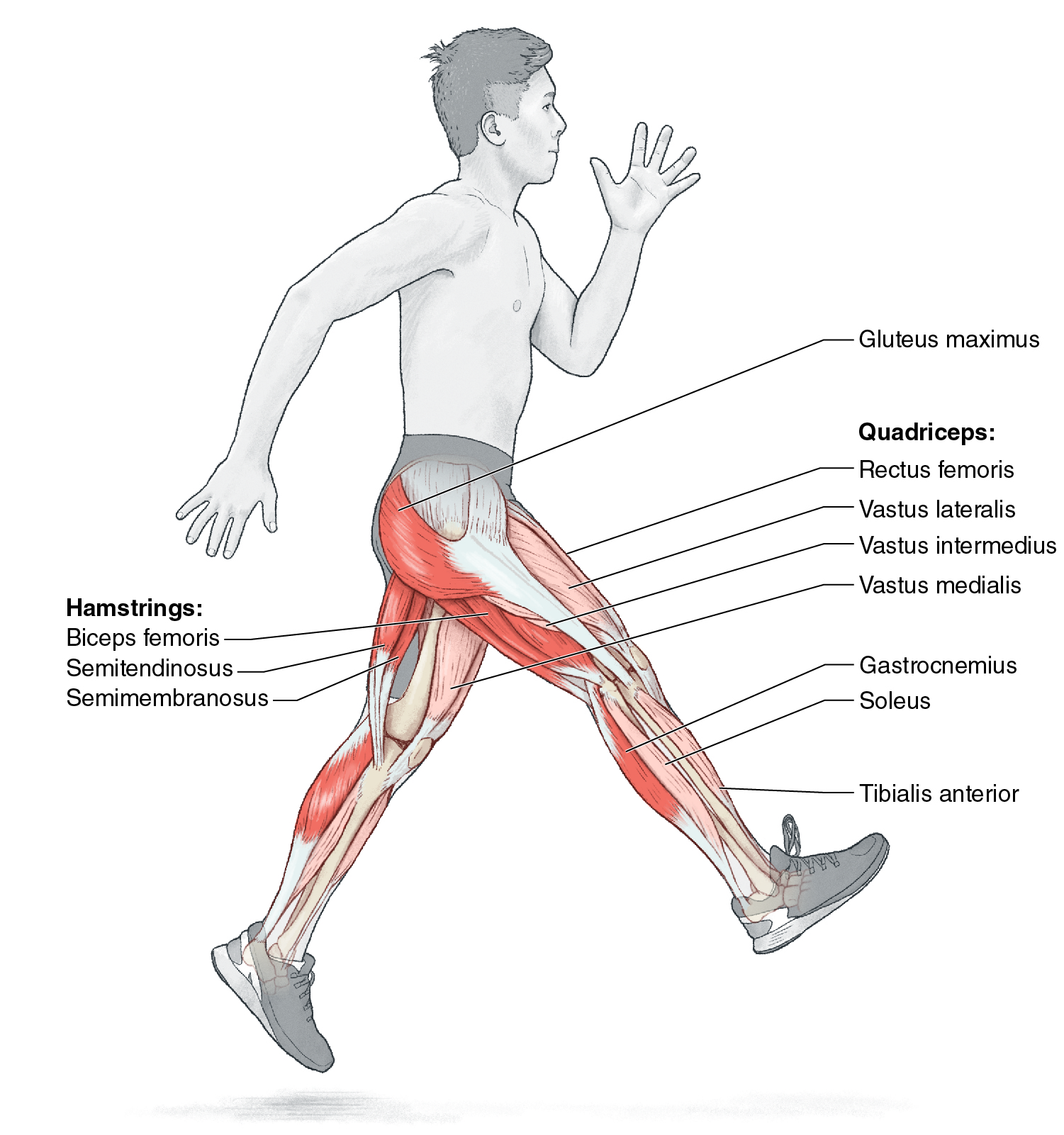

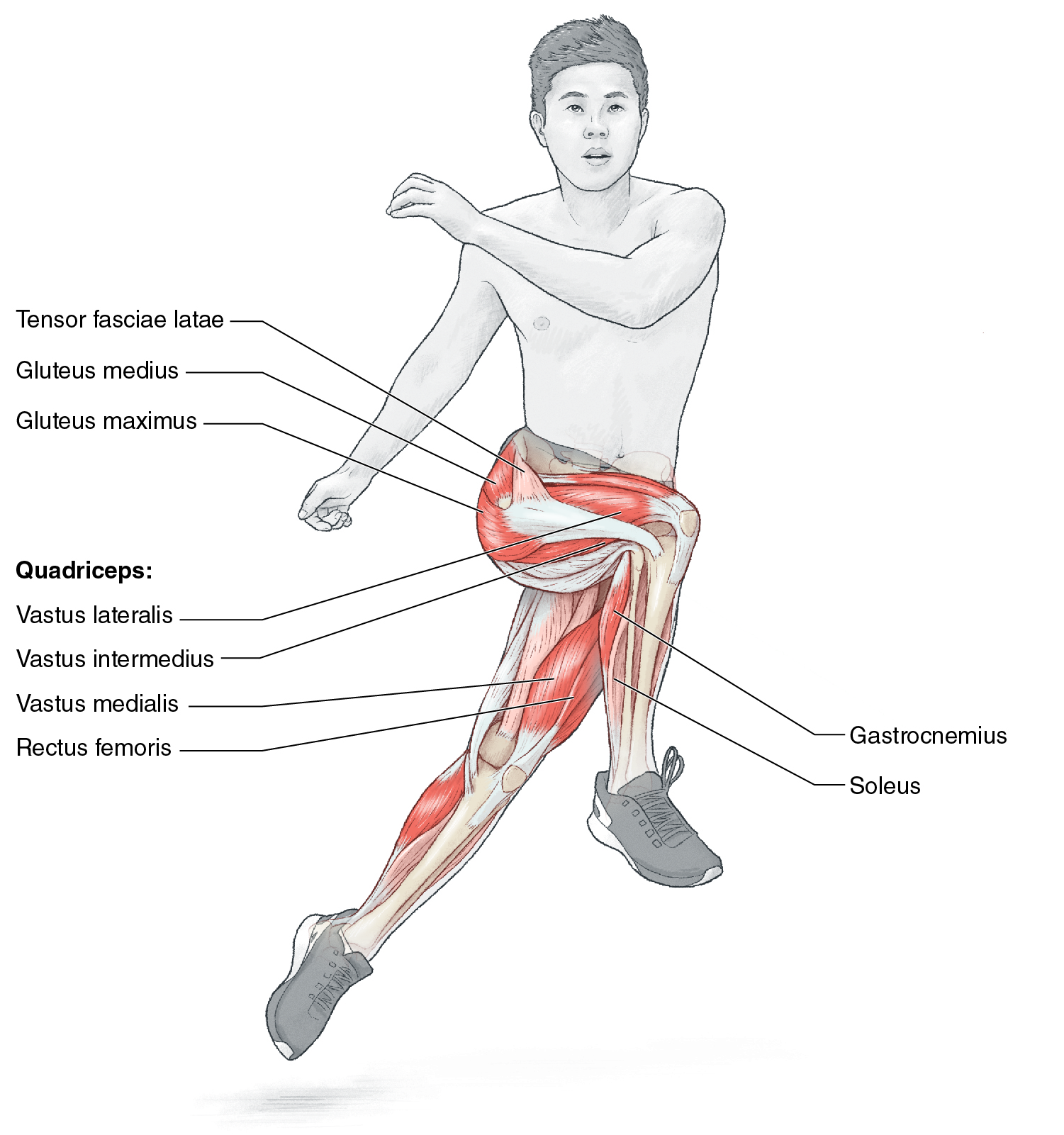

Muscles involved

Primary: Gluteus maximus, gastrocnemius, hamstrings (biceps femoris, semitendinosus, semimembranosus).

Secondary: Quadriceps (rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, vastus medialis), soleus, tibialis anterior.

Exercise notes

Bounding performed with limited knee flexion and the downward sweeping motion of the legs relies on elasticity in the lower legs and feet as well as significant hamstring strength. Straight-leg bounding teaches you to recruit the hamstrings as powerful hip extensors for propulsion in sprinting and jumping movements. The arms swing in an extended fashion to match the rhythm and action of the lower body.

2. Speed bound

Execution

- Stand with feet hip-width apart. Initiate first bound by driving the knee of the lead leg forward at a relatively flat trajectory. The opposite arm sweeps forward to match the range of the lead leg.

- Quickly draw the lead leg back toward the ground with the foot dorsiflexed to prepare for a dynamic landing a few inches in front of the centre of mass.

- Aim for a midfoot ground contact and a tall posture on landing with minimal knee flexion.

- Quickly drive the knee of the free leg forward to initiate the second bound and continue with this cyclical bounding movement for 20 to 30 metres in distance.

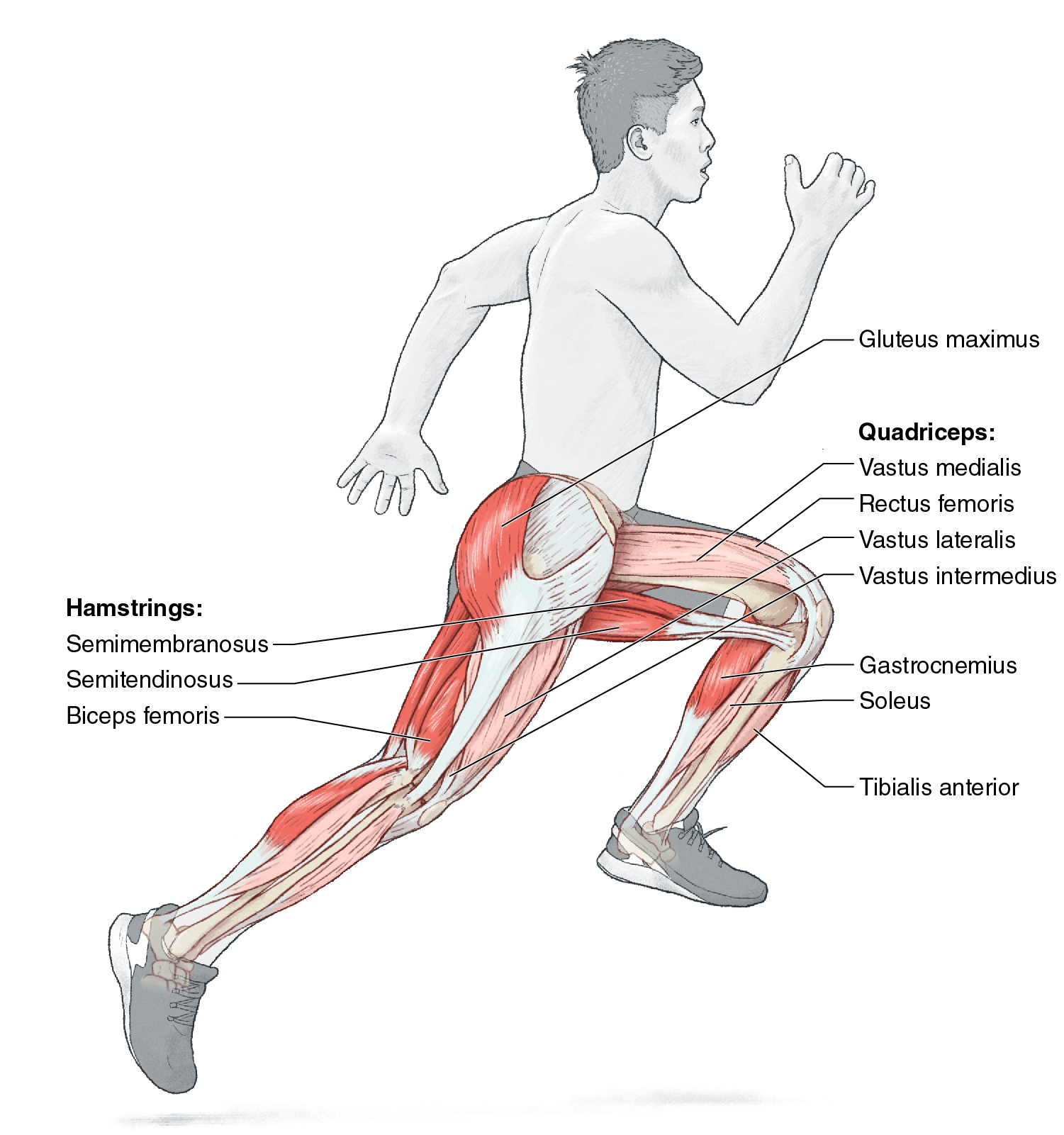

Muscles involved

Primary: Gluteus maximus, gastrocnemius, hamstrings (biceps femoris, semitendinosus, semimembranosus).

Secondary: Quadriceps (rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, vastus medialis), soleus, tibialis anterior.

Exercise notes

Bounding for speed will more closely resemble the action of a sprint stride. The trajectory of the bounds will be relatively flat with a greater emphasis on horizontal acceleration and velocity. The stride of speed bounds is exaggerated compared with a regular running stride, with a greater knee drive on each step and greater extension at the hip. Arm action in a speed bound matches the range and speed of the legs.

3. Uphill bound

Execution

- Stand with feet hip-width apart at the bottom of a gradual hill or incline. Initiate first bound by driving the knee of the lead leg forward to accelerate up the hill. The opposite arm sweeps forward to match the range of the lead leg.

- Quickly draw the lead leg back toward the ground with the foot dorsiflexed to prepare for a dynamic landing a few inches in front of the body.

- Aim for a midfoot ground contact and drive the body forward with a powerful hip extension motion.

- Quickly drive the knee of the free leg forward to initiate the second bound and continue with this cyclical bounding movement uphill for 20 to 30 metres.

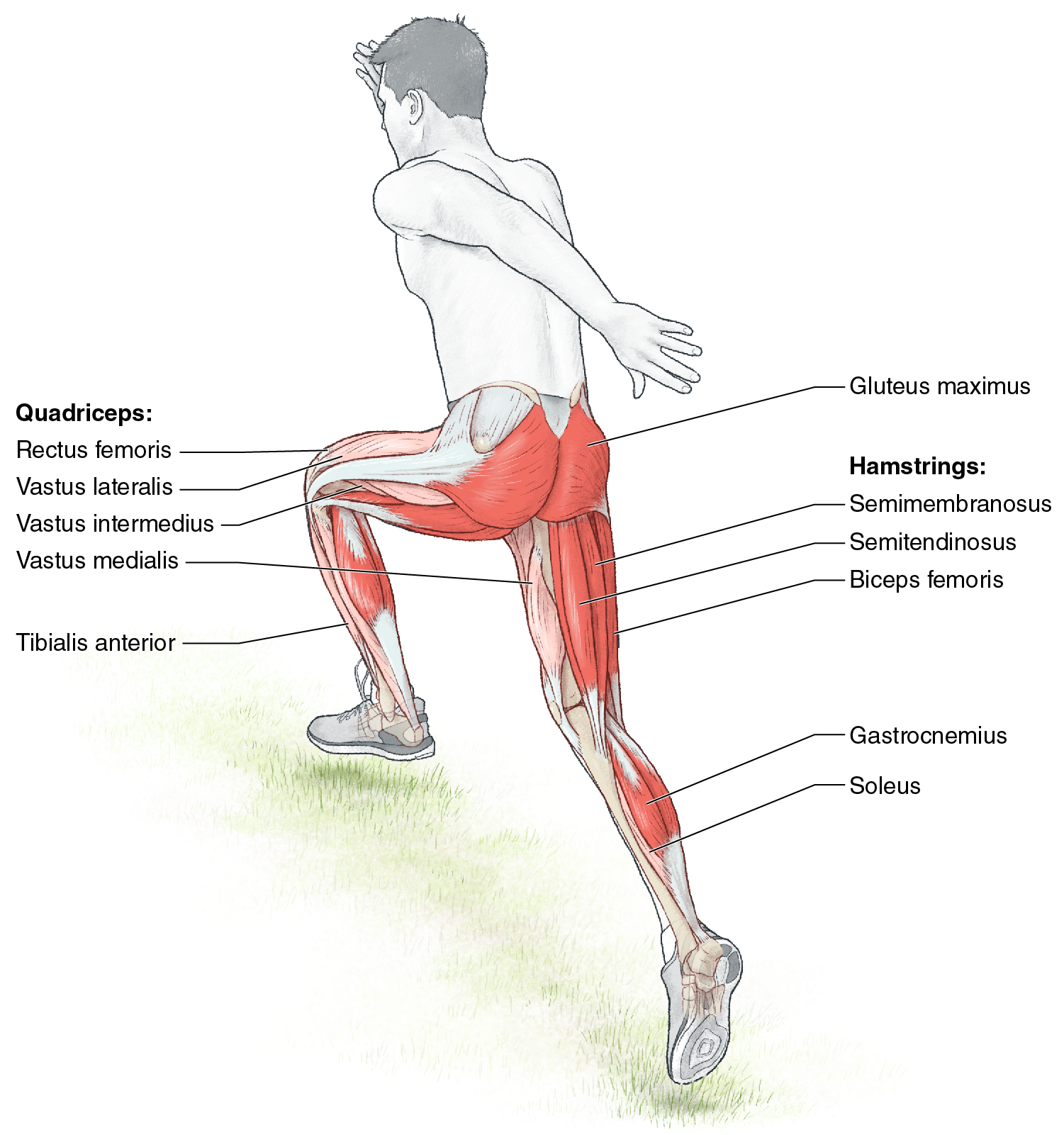

Muscles involved

Primary: Gluteus maximus, gastrocnemius, hamstrings (biceps femoris, semitendinosus, semimembranosus).

Secondary: Quadriceps (rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, vastus medialis), soleus, tibialis anterior.

Exercise notes

Bounding uphill is a useful means of teaching bounding and enhances hip extension during bounding, jumping and sprinting. Uphill bounding is also less stressful on the body than similar bounds on flat ground. The landing forces are reduced in an uphill scenario and provide an easier condition under which to learn the skill of bounding. It is important to select an uphill surface that is not slick or uneven, minimising the chance of slipping while executing the bounding steps.

Variation

Lateral uphill bound

You can perform uphill bounds with a slight side-to-side motion to add a lateral dimension to the exercise. The combination of powering up the hill and introducing a lateral push can simulate the acceleration requirements for ice hockey and speed skating, as well as agility movements in field sports.

4. Crossover bound

Execution

- Stand with feet hip-width apart. Initiate first bound by driving the knee of the lead leg forward and across the midline of the body. The opposite arm sweeps forward and across the midline of the body to match the range of the lead leg.

- The flight phase of the bound should be relatively short with an emphasis on quality of ground contact as opposed to bounding distance.

- As the lead leg descends toward the ground, prepare for ground contact with the foot dorsiflexed and execute a firm but quick midfoot landing.

- Quickly drive the knee of the free leg forward and across the midline of the body to initiate the second lateral crossover bound. Repeat this motion over 10 to 20 metres.

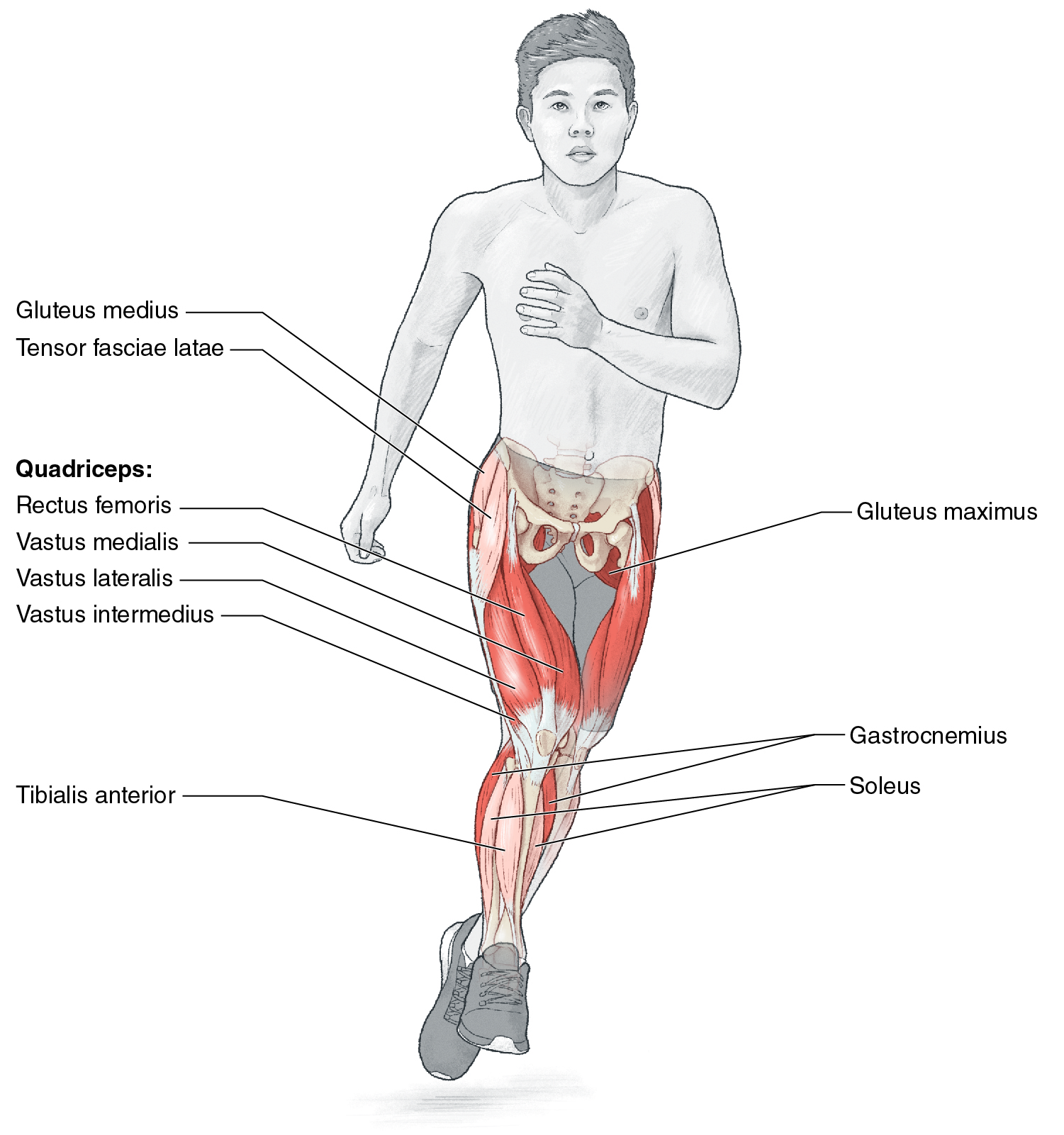

Muscles involved

Primary: Gluteus maximus, gastrocnemius, quadriceps (rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, vastus medialis).

Secondary: Gluteus medius, soleus, tibialis anterior, tensor fasciae latae.

Exercise notes

While lateral bounds can provide additional training of muscles on the lateral portions of the lower extremities, bounds that involve the legs crossing over the midline of the body place additional demands on the medial areas of the legs. This bounding exercise can simulate the mechanics and forces experienced during change of direction and cutting movements in many team sports such as soccer, basketball, American football, lacrosse and rugby. Stepping across the midline of the body to turn or change direction can place significant stresses on a single leg. You should introduce crossover bounding at submaximal intensities and over shorter distances initially to strengthen the required muscles and develop specific co-ordination. It is also important to execute these bounds on a training surface that is even and firm.

5. Carioca bound

Execution

- Stand lateral to the direction of travel. Initiate first bound by driving the knee of the far leg across the body for maximum distance.

- On landing, push laterally to accelerate the body sideways and attain distance on the next stride. Swing the arms in opposition to the legs to maintain balance and generate greater lateral power.

- Step behind the body on the next lateral stride. This stride will be of significantly less distance but will maintain the momentum of the lateral motion.

- Continue to bound across the body with both a stride in front and then a stride behind the body to accelerate over a distance of 10 to 30 metres.

Muscles involved

Primary: Gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gastrocnemius, quadriceps (rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, vastus medialis).

Secondary: Soleus, tensor fasciae latae, adductors (longus, magnus, brevis).

Exercise notes

This exercise incorporates an elongated stride pattern in the regular carioca drill by stepping across the body to provide lateral propulsion. In one stride, you step across the front of the body to generate downward force and horizontal propulsion. The next stride steps in behind the body to provide the same lateral propulsion. The stepping across and behind the body by strides creates rotational forces between the hips and shoulders because the arms counterrotate in relation to power produced by the legs. The range of motion by extremities covered in carioca bounding is much more significant than in the regular exercise because you cover more horizontal distance in each stride.

This is an extract taken from Plyometric Anatomy by Derek Hansen and Steve Kennelly by Human Kinetics. For a discount code to the text, please enter FP25 Visit: http://www.humankinetics.com/products/all-products/plyometric-anatomy